Abstract

When running a graph that was created from a Puppet manifest, mgmt has so far

used a workaround for each untranslatable resource. This workaround

involved an exec type resource, and shelling out to a variant of puppet

resource. Using the new puppet yamlresource receive subcommand, mgmt can now

send resources to a persistent Puppet process instead. The native support for

this is implemented through the new pseudo-resource pippet in mgmt.

It’s not meant to be used in mgmt code, but the Puppet code translator will

rely on it when required.

Ensuring semantics

I have blogged quite extensively about the Puppet compatibility

layers

for mgmt

in the past. They work because the most important core resource types from

Puppet (such as file and package) can be found in mgmt as well. We expect

that much Puppet code that is out there will be able to run through native mgmt

resources.

However, the full set of “core adjacent” types (like cron, sshkey,

interface, all the nagios resources etc.) is quite extensive.

The ecosystem of Forge modules with numerous custom resource types out there

is possibly even larger. It seems unlikely that all of them will eventually

be reflected by mgmt resources.

When running from Puppet code, any resources that mgmt does not support need to get synchronized in another way.

microwave_oven { "CN-4PK":

connected => true,

...

}

Additionally, some actual instances of mgmt supported types cannot be modeled correctly by mgmt, if they use properties that are exclusive to Puppet. For example, mgmt does not support downloading files from a Puppet server.

file { "/etc/motd":

source => "puppet:///modules/motd/default",

}

To provide for such resources, we implemented a

workaround that would

substitute such unsupported resources with a stand-in. The idea was to let

Puppet do the work of synchronizing these resources. The basic approach was

to generate exec resources that roughly do the following:

exec "substitute Cron[refresh-my-stuff]" {

cmd => "puppet resource cron refresh-my-stuff command=/path/to/script minute=...

The actual implementation is a little more involved (see article linked above),

and had me introduce the puppet yamlresource face. We have recently boosted

its performance using a new

subcommand puppet

yamlresource receive. It allows users or programs to send resource

descriptions directly to Puppet’s stdin stream. Puppet will sync these

resources directly and immediately, one by one.

In order to allow mgmt to take advantage of this latest addition, we needed to add three properties to mgmt with respect to its Puppet integration:

- mgmt needs to launch and track the Puppet receiver process.

- Individual resources in mgmt’s graph must be able to use this receiver.

- The Puppet manifest translator must emit such resources for mgmt.

Let’s look into each of these steps in turn.

Running a persistent Puppet

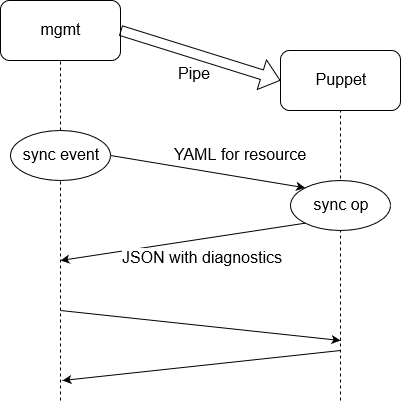

When using puppet yamlresource receive in order to connect Puppet to

another piece of software (in this case, mgmt), the processes communicate

via I/O pipes.

This design does not really follow a pattern that I have encountered in any of the projects I have worked on before. Fortunately, implementing it is very complex. The Puppet process is kicked off in the background, and mgmt just needs to be careful to hold on to its stdin and stdout I/O channels.

For easy management inside mgmt, I borrowed the Singleton pattern from object oriented programming. There is a global struct with a synchronized function that will retrieve it.

type pippetReceiver struct {

stdin io.WriteCloser

stdout io.ReadCloser

registerMutex sync.Mutex

applyMutex sync.Mutex

registered int

}

func getPippetReceiverInstance() *pippetReceiver {

for pippetReceiverInstance == nil {

pippetReceiverOnce.Do(func() { pippetReceiverInstance = &pippetReceiver{} })

}

return pippetReceiverInstance

}

pippetReceiverOnce is a sync.Once object

that makes this method thread safe. (“pippet” is not a typo and will be explained

in the next section.) The pippetReceiver is not properly initialized in this

moment. That does not happen before the first consumer registers itself.

func (obj *pippetReceiver) Register() error {

obj.registerMutex.Lock()

defer obj.registerMutex.Unlock()

obj.registered = obj.registered + 1

if obj.registered > 1 {

return nil

}

// count was increased from 0 to 1, we need to (re-)init

var err error

if err = obj.Init(); err != nil {

obj.registered = 0

}

return err

}

The obj.Init() method is responsible for starting Puppet and storing the

I/O streams for communication. The pippetReceiver object keeps a count of

registered users. This allows closing down the server process once all client

threads are finished.

Users of this pippetReceiver object are typically graph resources that rely on

Puppet. The next section (below) goes into more detail about these resources.

They call yet another function that implements the protocol of

puppet yamlresource receive. As parameters, this function takes the respective

resource details, and a reference to the pippetReceiver itself. This reference

takes the form of a minimalistic interface PippetRunner, which the

pippetReceiver implements.

type PippetRunner interface {

LockApply()

UnlockApply()

InputStream() io.WriteCloser

OutputStream() io.ReadCloser

}

// applyPippetRes does the actual work of making Puppet synchronize a resource.

func applyPippetRes(runner PippetRunner, resource *PippetRes) (bool, error) {

... #*

The LockApply and UnlockApply method just wrap the applyMutex from the

pippetReceiver struct, while InputStream and OutputStream are basically

getter methods for stdin and stdout in the same struct.

An aside on golang code design: The synchronization function was originally

implemented as a method of the pippetReceiver struct itself. That’s because

I was in the mind trap of thinking in terms of object oriented programming.

I had intended to build tests for all this code by generating a mock from the

(extensive) general interface that existed at that point. (The second mind trap

leading here was set by the absurdly powerful mocking that is available in

Ruby.)

What I had to realize is that this made testing very hard. In fact, I am dedicating a whole section to this topic towards the end of this article.

Graph nodes for Puppet

Now that mgmt is capable of running Puppet in the background, making it wait

for resources to sync, mgmt will need a way to also send these resources.

This cannot be done with an exec type node, because these write their

output to the system outside the mgmt process. The pipe to Puppet lives

within the mgmt process, though.

Besides, running an exec in order to write a resource description into

Puppet’s stdin stream would partly defeat the purpose. Overhead is to be

avoided. What is needed here is a dedicated resource type. Because it’s meant

to write information into a pipe to Puppet, it is named “Pippet”.

The structure of this type is very simple, designed specifically for easy marshalling.

type PippetRes struct {

...

Type string `yaml:"type" json:"type"`

Title string `yaml:"title" json:"title"`

Params string `yaml:"params" json:"params"`

runner *pippetReceiver

}

Notably, the Params are stored as a plain string, not a map. They are

expected to be presented as a YAML dictionary. This YAML will be passed

directly to Puppet, wrapped in a JSON object, along with the Type and

Title of the resource. Puppet does not really require the JSON wrapping,

but it is done in order to avoid any whitespace issues. (For more details,

I would direct you to the article about puppet yamlresource

receive again.)

This unusual practice is why the PippetRes struct contains JSON field tags.

You will not find these in most mgmt resource structs.

Pippet resources are not really supposed to be used in mgmt code. They are meant to result from Puppet manifest translations. The next section provides some details.

New graphs from Puppet

The ffrank-mgmtgraph Puppet module received a new “default translation” rule.

You can see the definition of this

rule

in the module code, written in the resource translator

DSL.

This rule replaces the original exec based workaround (which will be kept

for reasons of nostalgia, and possibly compatibility).

This is really all there is to it. As this changes the default behavior of

the mgmtgraph Puppet face, it was part of a “major” release (air quotes

courtesy of the fact that we’re still pre-1.0 release). We have dropped

compatibility with mgmt 0.0.20 and older (which do not have the pippet

resource yet). We also discovered some code cruft that got cleaned up,

but that is beyond the scope of this article.

A word about tests

When teaching mgmt to run the Puppet resource receiver process, I first approached the code with a “Ruby state of mind”. A struct with fields for all the runtime data was created, with methods to perform initialization, tracking for resources that use Puppet this way, and the actual communication. My first idea for building tests for this whole construct involved generating a mock implementation for this full interface. It would stub the resource synchronization method, so that no actual Puppet process would be needed for testing.

What I had to realize was that this approach would have made for very brittle tests. My stubbing options would have essentially circumvented all the interesting code paths altogether, and the entire logic around dealing with Puppet’s output would have gone untested. The whole endeavor was doomed from the beginning, which I did not realize until I was trying to write an actual test.

In the world of Ruby testing, RSpec offers a profoundly easy way to perform stubbing at arbitrary levels of granularity. This makes it possible to come up with some amazingly specific test cases with little effort. In golang, this is not quite as straight forward, and writing testable code involves different approaches.

I started reading up on the topic of mocking in golang, and found that it was much less ubiquitous than in the Ruby context. Many opinion pieces allude to “dependency injection”, making it appear as somewhat of a superior alternative (my findings so far have been that the two actually complement one another). The approach seemed fascinating, so I started looking into dependency injection as a basic design pattern. To any reader who is struggling with the switch to golang themselves, I can emphatically recommend to do the same.

The document that finally clicked for me is this blog entry about testable golang programs by Karl Matthias. Not only does it explain the ideas of dependency injection very vividly, it also finally made me understand some of the ways in which golang uses interfaces.

I went ahead and redesigned the resource synchronization method explicitly so that dependency injection would be possible. For testing, I built my own custom mock implementation of the injectable interface. Once again, it goes to show that it’s worthwhile to take the time and build sensible tests for your code. You may learn something along the way.

Summary

Both mgmt and the ffrank-mgmtgraph Puppet module were significantly enhanced

to allow better performance under certain conditions. Puppet also got a

versatile new feature with the yamlresource receive command, which might

enable some other hacks in the future.

With these pieces in place, we are finally approaching our goal of making it

possible to run arbitrary Puppet code through mgmt.